Information/Write-up

The Solitude Trilogy is a collection of three hour-long radio documentaries produced by Canadian pianist Glenn Gould (1932–1982) for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (and later a film collaboration between the CBC and PBS). Gould produced the documentaries as individual works between 1967 and 1977, then collected them under the title Solitude Trilogy, reflecting the theme of "withdrawal from the world" that unites the pieces. He said that they are "as close to an autobiographical statement as I intend to get in radio".[3]

The three pieces employ Gould's idiosyncratic technique of simultaneously playing the voices of two or more people, each of whom speaks a monologue to an unheard interviewer. Gould called this method "contrapuntal" radio. (The term contrapuntal normally applies to music in which independent melody lines play simultaneously; this type of music, exemplified by J. S. Bach, was the major part of Gould's repertoire.)

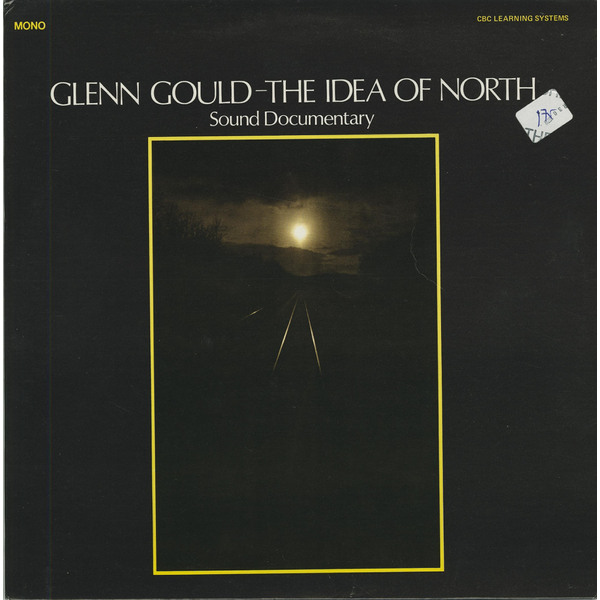

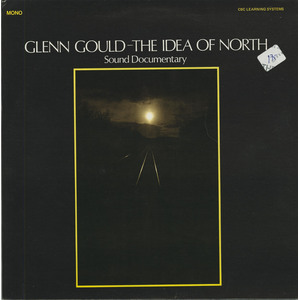

The first and most well-known of the documentaries is The Idea of North, produced in 1967, in which five speakers provide contrasting views of Northern Canada. PBS aired an experimental film based on it, directed by Judith Pearlman, in 1970, its first co-production with CBC. To open the documentary, Gould says:

I've long been intrigued by that incredible tapestry of tundra and taiga which constitutes the Arctic and sub-Arctic of our country. I've read about it, written about it, and even pulled up my parka once and gone there. Yet like all but a very few Canadians I've had no real experience of the North. I've remained, of necessity, an outsider. And the North has remained for me, a convenient place to dream about, spin tall tales about, and, in the end, avoid. This programme, however, brings together some remarkable people who have had a direct confrontation with that northern third of Canada, who've lived and worked there and in whose lives the North has played a very vital role.

In 1969, Gould made The Latecomers, about life in Newfoundland outports, and the province's program to encourage residents to urbanize.

The third documentary, 1977's The Quiet in the Land, is a portrait of Russian Mennonites in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The speakers discuss the influence of contemporary society on traditional Mennonite values.

The documentaries employ ambient sound and music. The rumbling of a train is heard frequently in The Idea of North, the ocean in The Latecomers, and a church sermon and choir in The Quiet in the Land. Again referring to music, Gould called these elements ostinatos.

The Idea of North ends with the last movement of Karajan's recording of Sibelius' Symphony no. 5 in E flat major, the only use of a complete movement from the classical repertoire in the trilogy. Just like the Sibelius symphony ending The Idea of North, The Quiet in the Land can also be said to be in the key of E-flat major, as it uses and sometimes superimposes various pieces in that key: the sarabande from Bach's Cello Suite No. 4 in E-flat, a church hymn, a rehearsal of a choral piece for children's choir and harp ("As Dew in Aprille" from Britten's A Ceremony of Carols), and Janis Joplin's song "Mercedes Benz".

Liner notes

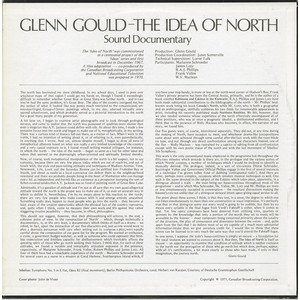

The ‘Idea of North’ was commissioned as a centennial project of the ‘Ideas’ series and first broadcast in December 1967.

A film adaptation — co-produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and National Educational Television — was prepared in 1970.

Production: Glenn Gould

Production Coordination: Janet Somerville

Technical Supervision: Lorne Tulk

Participants:

Marianne Schroeder

James Lotz

R.A.J. Phillips

Frank Vallee

W.V. Maclean

The north has fascinated me since childhood. In my school days, I used to pore over whichever maps of that region I could get my hands on, though I found it exceedingly difficult to remember whether Great Bear or Great Slave was further north — and in case you’ve had the same problem, it’s Great Bear. The idea of the country intrigued me, but my notion of what it looked like was pretty much restricted to romanticized, art-nouveau-inged, Group-of-Seven paintings which, in my day, adorned virtually every second school-room, and which probably served as a pictorial introduction to the north for a great many people of my generation.

A bit later on, I began to examine aerial photographs and to look through geological surveys, and came to realize that the north was possessed of qualities more elusive than even a magician like A.Y. Jackson could define with oils. At about this time, I made a few tentative forays into the north and began to make use of it, metaphorically, in my writing. There was a curious kind of literary fall-out there, as a matter of fact. When I went to the north, I had no intention of writing about it, or of referring to it, even parenthetically, in anything that I wrote. And yet, almost despite myself, I began to draw all sorts of metaphorical allusions based on what was really a very limited knowledge of the country and a very casual exposure to it. I found myself writing musical critiques, for instance, in which the north — the idea of the north — began to serve as a foil for other ideas and values that seemed to me depressingly urban-oriented and spiritually limited thereby.

Now, of course, such metaphorical manipulation of the north is a bit suspect, not to say romantic, because there are very few places today which are out of reach by, and out of touch with, the style and pace-setting attitudes and techniques of Madison Avenue, Time, Newsweek, Life, Look and the Saturday Review can be airlifted into Frobisher Bay or Inuvik, just about as easily as a local contractor can deliver them to the neighbourhood newsstand and there are probably people living in the heart of Manhattan who can manage every bit as independent and hermit-like an existence as a prospector tramping the north of Lichfield encountered through that A.Y. Jackson was so fond of painting north of Great Bear Lake. Admittedly, it’s a question of attitude and I’m not at all sure that my own quasi-allegorical attitude toward the north is the proper way to make use of it, or even an accurate way in which to define it. Nevertheless, I’m by no means alone in this reaction to the north; there are very few people who make contact with it and emerge entirely unscathed. Something really does happen to most people who go into the north — they become at least aware of the creative opportunity which the physical fact of the country represents

No Comments