Information/Write-up

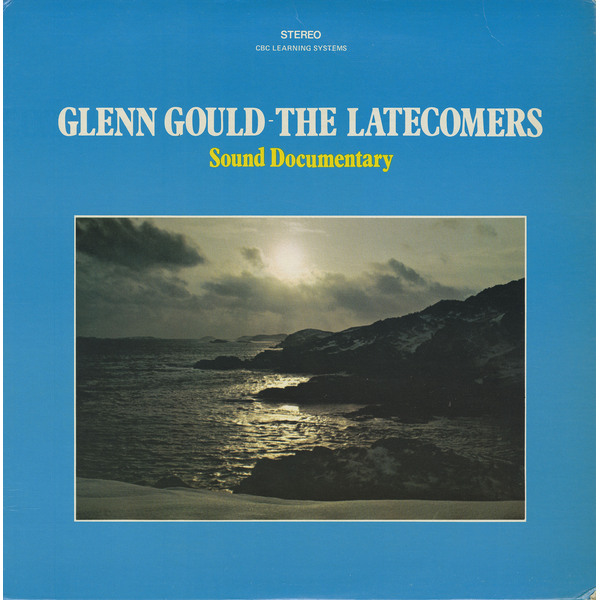

The Solitude Trilogy is a collection of three hour-long radio documentaries produced by Canadian pianist Glenn Gould (1932–1982) for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (and later a film collaboration between the CBC and PBS). Gould produced the documentaries as individual works between 1967 and 1977, then collected them under the title Solitude Trilogy, reflecting the theme of "withdrawal from the world" that unites the pieces. He said that they are "as close to an autobiographical statement as I intend to get in radio".[3]

The three pieces employ Gould's idiosyncratic technique of simultaneously playing the voices of two or more people, each of whom speaks a monologue to an unheard interviewer. Gould called this method "contrapuntal" radio. (The term contrapuntal normally applies to music in which independent melody lines play simultaneously; this type of music, exemplified by J. S. Bach, was the major part of Gould's repertoire.)

The first and most well-known of the documentaries is The Idea of North, produced in 1967, in which five speakers provide contrasting views of Northern Canada. PBS aired an experimental film based on it, directed by Judith Pearlman, in 1970, its first co-production with CBC. To open the documentary, Gould says:

I've long been intrigued by that incredible tapestry of tundra and taiga which constitutes the Arctic and sub-Arctic of our country. I've read about it, written about it, and even pulled up my parka once and gone there. Yet like all but a very few Canadians I've had no real experience of the North. I've remained, of necessity, an outsider. And the North has remained for me, a convenient place to dream about, spin tall tales about, and, in the end, avoid. This programme, however, brings together some remarkable people who have had a direct confrontation with that northern third of Canada, who've lived and worked there and in whose lives the North has played a very vital role.

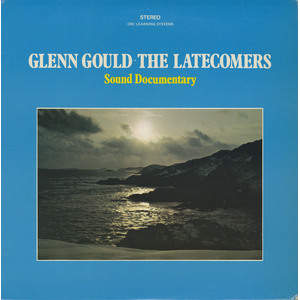

In 1969, Gould made The Latecomers, about life in Newfoundland outports, and the province's program to encourage residents to urbanize.

The third documentary, 1977's The Quiet in the Land, is a portrait of Russian Mennonites in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The speakers discuss the influence of contemporary society on traditional Mennonite values.

The documentaries employ ambient sound and music. The rumbling of a train is heard frequently in The Idea of North, the ocean in The Latecomers, and a church sermon and choir in The Quiet in the Land. Again referring to music, Gould called these elements ostinatos.

The Idea of North ends with the last movement of Karajan's recording of Sibelius' Symphony no. 5 in E flat major, the only use of a complete movement from the classical repertoire in the trilogy. Just like the Sibelius symphony ending The Idea of North, The Quiet in the Land can also be said to be in the key of E-flat major, as it uses and sometimes superimposes various pieces in that key: the sarabande from Bach's Cello Suite No. 4 in E-flat, a church hymn, a rehearsal of a choral piece for children's choir and harp ("As Dew in Aprille" from Britten's A Ceremony of Carols), and Janis Joplin's song "Mercedes Benz".

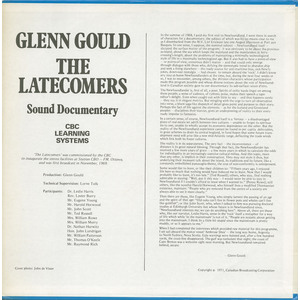

‘The Latecomers’ was commissioned by the CBC to inaugurate the stereo facilities at Station CBO – FM, Ottawa, and was first broadcast in November, 1969.

Production: Glenn Gould

Technical Supervision: Lorne Tulk

Participants:

Dr. Leslie Harris

Rev. Lester Burry

Mr. Eugene Young

Mr. Harold Horwood

Mr. John Scott

Mr. Ted Russell

Mrs. William Rowe

Mrs. William Morry

Dr. Nathan Hurwitz

Hon. John Lundrigan

Mr. William Patterson

Mr. Thomas O’Keefe

Mr. Raymond Rich

Cover photo: John de Visser

In the summer of 1968, I paid my first visit to Newfoundland. I went there in search of characters for a documentary, the subject of which was by no means clear to me as I disembarked from the M.V. Lief Erickson late one August afternoon at Port aux Basques. In one sense, I suppose, the nominal subject — Newfoundland itself — dictated the surface matter of the program; it was obviously to be about the province-as-island, about the sea which keeps the main land and the mainlanders at ferry-crossings-length, about the problems of maintaining a minimally technologized. But it also had to have a point-of-view — or points-of-view, consensus didn’t matter — and that could only emerge through dialogue with those who, defying the stereotypic trend to abandon ship and seek a living elsewhere — the ready source for anti-maritime bias, sick-Newfy jokes, down-east nostalgia — had chosen to remain aboard the ‘rock’. I didn’t know any stay-at-home Newfoundlanders at the time, but, during the next four weeks or so, I was to encounter, among others, the thirteen characters whose participation made this programme possible and whose diverse notions about the role of Newfoundland in Canadian society gave to our documentary its sub-surface raison d’etre.

The Newfoundlander is, first of all, a poet. Spirits of celtic bards linger among these people; a sense of cadence, of rhythmic poise, makes their speech a trademark of editor’s delight. Even when caught out with little to say — and that happens rarely — they say it in elegant metrics. But mingling with the urge to turn all observation into verse, a blunt sage-like dispatch of detail gives point and purpose to their story. Perhaps the fact of life against the elements — as for the Iceland and Greenland peoples — disciplines their stanzas, gives an underpinning of reality to their ever-ready impulse to fantasize.

In a certain sense, of course, Newfoundland itself is a fantasy — a disadvantaged piece of real-estate set adrift between two cultures — unable to forget its spiritual tie to one, unable to wholly accept its economic dependence on the other. But the reality of the Newfoundland experience cannot be found in per capita debt-tables, in great schemes to drain its central bogland, in fond hopes that some future trans-shipment need will arise like a new mid-Atlantic range, deflecting the trade winds which link both its foster cultures.

The reality is in its separateness. The very fact — the inconvenience — of distance is its great natural blessing. Through that fact, the Newfoundlander has received a few more years of grace — a few more years in which to calculate the odds for individuality in an increasingly coercive cultural milieu. And this topic, more than any other, is implicit in their conversation. They may not style it thus, but underlying their incessant talk about the island, its traditions and its future, like a constantly embellished passacaglia-theme, the cost of non-conformity is omnipresent.

Some would like to leave, or like their children to: “Fifteen years ago, I enjoyed life here so much that nothing would have induced me to leave. Now that I would probably like to leave, it’s too late.” (Ted Russell); others, who stay, find nothing admirable in staying: “Well, put it this way — I would never be able to stay in Newfoundland if I couldn’t afford to leave when I wanted to.” (Penny Rowe); still others, like the novelist Harold Horwood, who himself lives a modified Thoreauvian existence, maintain: “People who are removed from the centre of a society are always able to see it more clearly.”

Then there are those, like Eugene Young, who simply lament the passing of an age and the slighting of that age: “Old oaks can’t live in flower pots and whales can’t live like goldfish”; or like John Scott, who, when I talked to him was pursuing doctoral studies at Edinburgh University but whose future is in Newfoundland since, “Newfoundland interests me; we can do anything here.” Above all, there are those who, like our narrator, Leslie Harris, sense in the ‘rock’ itself a metaphor for a way of life which in the mainstream is not of it. “People are ecstatic about getting into the mainstream. I think it’s a little bit stupid since the mainstream is pretty muddy, or so it appears to me.”

When I had completed the interviews which provided raw material for this programme, I set sail aboard the motor vessel ‘Ambrose Shea’ — the long way home, Argentina to North Sydney, Nova Scotia. Gale warnings were hoisted and, after a few hundred yards, the coast-line disappeared. The gulf was turbulent that night; the coast of Cape Breton was a welcome sight next morning. But Newfoundland remained behind, secure.

-Glenn Gould

No Comments