Information/Write-up

The Diodes sit right at the fault line where Toronto’s art-school ferment flipped into something louder, faster, and suddenly international. They weren’t a band that arrived after the fact to document a “scene” — they helped build the room the scene happened in, at a moment when Canada didn’t yet have the infrastructure (clubs, radio, indie labels, press support) that would later make alternative music feel normal. In 1977, it wasn’t.

The pre-history begins inside the Ontario College of Art’s orbit in late 1976. Guitarists John Catto and Ian Mackay — painters with a media-arts curiosity for sound as an idea — linked up with bassist David Clarkson and met Paul Robinson, an art-history student who seemed to materialize fully formed: loud, opinionated, and magnetically committed to the new music pouring out of New York. Robinson was born in Newton, Massachusetts, studied at the Boston Museum School, drifted through Montréal in 1974, and eventually landed at York University in Toronto. He wasn’t a “trained frontman” so much as a force of will — the kind of singer who doesn’t wait for permission to exist.

The Diodes were still forming when they were booked into a situation that would become legend. The Talking Heads were coming to Toronto; the fledgling band snagged an opening slot at OCA with little more than raw intent, minimal chops, and the kind of collective momentum that punk made possible. That first era was messy by design: a rush to make something new with whatever was at hand, in a city that hadn’t yet decided it wanted bands like this.

By early 1977 the first stable working lineup began to take shape, and the Diodes’ ambitions quickly outgrew the normal routes. Toronto clubs didn’t know what to do with them; there wasn’t yet a recognized underground circuit to absorb the noise. So the Diodes, with manager Ralph Alfonso, did what would become the defining act of their mythology and their practical legacy: they converted their rehearsal space at 15 Duncan Street into Crash ’n’ Burn, the first punk club in Canada. Open only on Fridays and Saturdays, it was improvised architecture and pure intent — white-painted floors, exposed pipes, crude benches, a bar knocked together from old doors, beer in paper cups, and a stage that felt one shove away from collapse. It wasn’t just a venue. It was proof that if the city wouldn’t provide a place for this music, the bands would simply build one.

Crash ’n’ Burn also accelerated everything: the local groups who pitched in to make it functional, the touring bands who suddenly had a Toronto address, the press who came sniffing for a story, and the tensions that followed when curiosity and sensationalism collided with a young crowd expecting chaos. Violence became part of the era’s shorthand — sometimes imported, sometimes provoked — and the Diodes were constantly forced to “answer for” a movement that the mainstream had already decided to misunderstand. Yet the club’s impact was immediate. It stamped Toronto onto the new music map, created a point of contact between local bands and the wider punk network, and made the Diodes the most visible lightning rod of the city’s first punk eruption.

Inside the band, the lineup shifted as the stakes rose. Clarkson stepped away; a brief bass interlude brought in John Korvette (John Corbett), and then Mackay moved to bass. With John Hamilton on drums, the quartet of Robinson (vocals), Catto (guitars), Mackay (bass), and Hamilton (drums) became the core lineup that mattered most to the band’s first recorded statement — and to Canadian punk history.

In August 1977, CBS Records Canada — newly energized after seeing the U.K. punk explosion first-hand — signed the Diodes. The timing was surreal: the label was eager, the band was ready, and the broader Canadian music industry was still acting like “alternative” didn’t exist. CBS moved quickly, releasing The Diodes in October 1977, astonishingly early in punk’s first wave — ahead of some of the era’s better-known contemporaries. The album was recorded with a “live off the floor” urgency and a clarity that separated them from caricature. They weren’t interested in wallowing in the standard punk clichés; their lyrics leaned into suburban psychic dread, media saturation, status fantasies, and pop culture as a kind of modern haunt — abstract imagery, television, tennis, movie stardom, and the odd, clinical mood of late-’70s modern life.

The band’s first single became their first public contradiction: a manic, weaponized cover of “Red Rubber Ball.” It was the Diodes’ way of turning an old pop artifact inside out — a bright 1960s melody re-wired with punk velocity and attitude. In Canada it charted modestly (enough to be historic in context), but in the U.S. it found a receptive “new wave” audience and proved the band could travel outside the local narrative Toronto press had built around them.

That international pull was real. The Diodes were positioned between New York and London, absorbing American CBGB’s energy and returning home charged by U.K. signals. They played New York, including a notable two-night headline at Max’s Kansas City in late 1977, and they hit the road early in 1978 with the kind of bill that instantly reframes a band’s credibility: The Ramones and The Runaways at Chicago’s Aragon Ballroom, where the Diodes earned an encore. Their debut LP circulated outside Canada as an import and appeared in European markets, while U.K. tastemakers treated the band less like a curiosity and more like a serious new voice in the wave.

By 1978, the Diodes had become the rare Canadian punk group receiving significant outside validation while still pushing against resistance at home. The irony was brutal: the band could be reviewed, played, and admired abroad while Canadian radio and retail gatekeepers warned that “aggressive” music would repel listeners and customers. The Diodes were early — too early for the domestic system to know what to do with them — and they paid for that timing even while they benefitted from the doors their visibility pried open for everyone who followed.

Musically, they were already evolving beyond the narrow “punk” box people kept trying to stuff them into. Catto’s guitar work — loud, inventive, and textural — gave the band a distinctive edge: power-chords that could hit like hard rock, then twist into odd, unnerving shapes. Hamilton wasn’t just keeping time; he brought arrangement instincts, vocals, and keyboards into the Diodes’ palette. Robinson, meanwhile, was a performer as much as a singer — an actor and mime-like presence who could command a room through movement, confrontation, and charisma even when critics nit-picked his vocal limitations. The Diodes’ real argument was always made on stage: high-energy, physical, relentless, and smart enough to be funny without blinking.

Their signature song arrived in this period: “Tired of Waking Up Tired.” It caught fire as a single and became the band’s defining anthem — a track that could live in punk, power pop, and “new rock” at once. British writers heard mid-’60s DNA refracted through a futuristic lens; American critics heard the delight of melody and fuzz with the urgency of new wave. The Diodes, in other words, were doing what the best first-wave bands did: stealing tools from the past, throwing them into the present, and accidentally building the future.

But the band’s story is also a case study in how quickly the music industry can turn on a group it doesn’t understand. As punk’s public narrative shifted toward “new wave” by the end of the decade, the Diodes found themselves caught in a corporate logic trap: too punk for conservative domestic gatekeepers, not “punk enough” for executives elsewhere, and too musically restless to play the role assigned to them. Their second album — recorded in 1978 — became the point of crisis. CBS shelved it, then dropped them in early 1979, and the band went public with their frustration. For a moment, it looked like a “swan song”: a final show planned at OCA, contracts terminated, the story ending where it began.

Instead, the Diodes refused to end cleanly. The shelved album eventually emerged as Released (Epic, 1979), reflecting both the absurdity and the persistence of the moment: a record the label didn’t believe in, suddenly issued anyway after circumstances shifted. By then, the lineup had changed: Hamilton departed, and drummer Mike Lengyell brought a tougher, more muscular live edge that pushed the band toward a harder, more back-to-basics attack — the version many audiences remembered as their most ferocious stage incarnation.

That momentum carried into the next phase: Action-Reaction (1980), issued through Orient/RCA distribution. It captured a Diodes that had lived through the initial punk blast and come out tougher, louder, and more road-hardened. They continued to tour widely, sharing stages with major acts of the era, and proving again and again that whatever the records suggested, the Diodes were a live band built for impact.

By 1982, their original era had largely burned out, but the catalogue kept mutating through reconfigurations and archival releases. Survivors (Fringe Product, 1982) gathered material that widened the story beyond the canonical albums, reinforcing how much the band’s best work wasn’t always aligned with what labels wanted at the time. Years later, their CBS/Epic recordings would be re-contextualized properly through anthology releases that finally framed the Diodes as what they were: first-wave pioneers whose “too early” timing in Canada looked, in hindsight, like the opening move.

If there’s a single thread running through the Diodes’ entire arc, it’s that they behaved like a modern band before the Canadian industry had fully invented the modern support system. They engineered their own infrastructure (Crash ’n’ Burn), forced major-label attention onto “new music” in Canada earlier than the market wanted, proved they could compete internationally on stage and in press, and left behind songs — especially “Tired of Waking Up Tired” — that outlived the scene arguments that once tried to contain them. Their story isn’t only about “Toronto’s first punk band”; it’s about the moment Canada’s musical underground stopped asking to be let in and started kicking open doors.

-Robert Williston

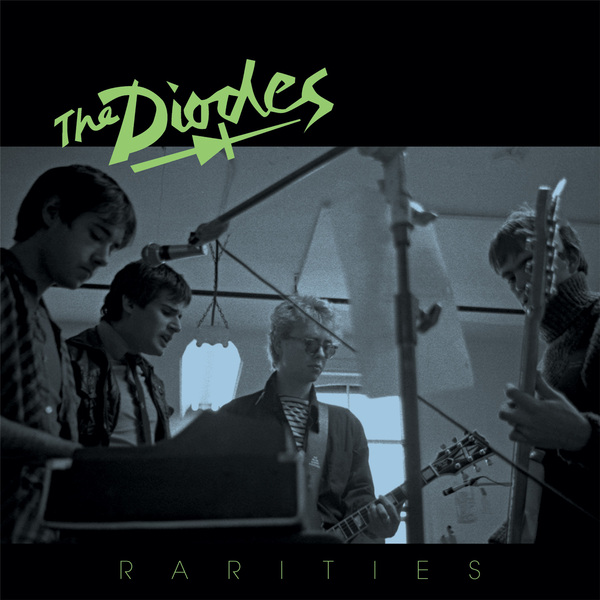

Canadian punk rock history! This exclusive collection of rare Diodes tracks contains alt versions, demos, and archive treasures, including two versions of the band's hit Tired Of Waking Up Tired. The art direction and mastering process was overseen by the The Diodes, and the beautiful packaging collects rare photos from Ralph Alfonso and General Idea. An essential collection of one of Canada's best punk rock acts.

No Comments